Yes, Wordle is Part of the Metaverse Too

An optimistic take on the metaverse by looking at that catchy word game everyone is talking about

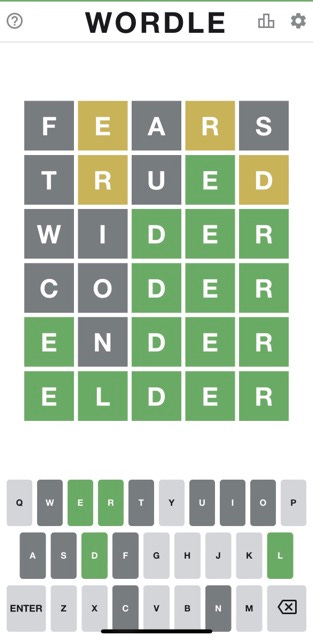

If you squint hard enough, the output of a Wordle grid looks something like an NFT.

It’s a semi-unique output as the result of an algorithm, a key, and human input. The Wordle shapes, like other popular NFTs, are recombinations of a basic sort of visual form. But instead of Bored Apes, they’re 5x(1-6) grids. The output isn’t mathematically unique (or saved on a blockchain), but experientially they serve somewhat similar ends. They’re both visual representations of a user’s interaction with an algorithm in this sort of distinct way. And Wordle, like NFTs are supposed to be*, is transportable between platforms. I can share it on the messaging service of my choice, happily. Wordle, in some cultures, is also enjoying some of its own backlash and has already been gobbled up by the New York Times which is varnishing its subscription creds at the same time that giants like Microsoft and Playstation make their moves.

This is all somewhat tongue-in-cheek but I don’t think the differences are so great we can’t learn something from Wordle. I think framing Wordle this way might help get at some of what people see in NFTs. Digital spaces really do have a permanence problem. But there are probably a few points that you’re thinking that Wordle definitely doesn’t fit into this whole “metaverse” thing. Namely, it’s a text-based game and the metaverse is supposed to be visual, that even so it’s a game you play by yourself, and there’s nothing that differentiates Wordle from being say, a huge fad.

What is the Metaverse Though?

I think Ben Thompson’s argument that the internet already is the metaverse pretty compelling. Namely that there’s nothing distinct about the difference between “a metaverse” and the internet, it already satisfies all of the conditions. And if that’s the case then the metaverse already is capable of being something that isn’t necessarily a 3d facsimile of the world. Where I disagree is here:

What makes “The Metaverse” unique, then, is that it is the Internet best experienced in virtual reality. This, though, will take time; I expect that the first virtual reality experiences will be individual metaverses, tied together by the Internet as we experience it today.

Immersion in pop culture tends to be talked about purely in visual terms. We call things more immersive if their visual representation is more accurate, lifelike, and less pixelated. And visual representation is certainly one element of immersion, but the function of immersion is not purely a visual one. Immersion is a state that the human brain hits when the cohesiveness of our actions mesh with the expectations of our senses and the world around us. Metaverses as an evolution represent something more of a shared digital reality that multiple people are engaging with at any one time. It’s the existence of artifacts and agents that multiple people can look at as a shared artifact that represents a history of a place that has existed outside of their heads and is separate from the physical world.

But this also doesn’t mean we have metaverses lurking around every corner. The reason slack isn’t a metaverse is that we’re not really playing the same game by the same rules. It’s a communication point where we all talk about stuff but we’re governed by different goals, are often moving in different directions, and have completely different boundaries and expectations.

The core is that we’re all interacting with the same set of rules at the same time. What good graphics are to immersion, 3d is to presence. They both represent one way of creating a core component of the experience (enjoyment for immersion and shared reality for presence) but are by no means the only way to do that. Simply put, a metaverse should care about its history.

The concept that presence is based on a 3-d facsimile of a thing presupposes that the impact of the physical world is visual and not multi-sensory and experiential. When we say we feel the presence of someone who we’ve lost, we don’t tend to only mean “something that visually reminds us of them”. We also mean a set of behaviors or actions that reminds us of them. I.e. when we say something like “you remind of someone” we often mean that they are behaving in an uncanny way. Or when I hear the wind chimes in the fig tree at my parent’s house I imagine where my childhood doggo used to sit while we tended the garden. I don’t feel that way whenever I hear any windchime in the world: it’s the combination of location, sound, the wind, and how I feel when I’m there. It’s not just the visual component. It’s also why we sometimes ask people on their phones to put them away and “be present”. The fact that they’re in our line of vision is obscured by their lack of behavior, they might as well not be.

The internet enables so many sharing features that are truly spectacular. When the pandemic hit my regular board gaming group basically had to shut down. Playing online became a way to continue sharing those moments together and spending time together. But the difference when the end of the games couldn’t have been more stark. When we were in person we’d sit around the table and look at the board, recreating the steps in our head or talking about particular elements and strategies. Online it became much harder to do so. While the computer helped us play more complex games more easily, it also made the experience of playing so much more impermanent. When the game ended we’d often get a summary screen and then we’d close the browser and it’d be as if it hadn’t even happened. I’m not asking for a return to the cleanup of multi-component but it’s nice to be able to look back at an artifact and spark a memory of an experience. And frankly, it’s just really to feel that sense of “this is a thing that happened” with a lot of digital games. Achievements point to some of this, but they’re also pre-chosen by the designer not by our experiences of playing the game. This is a real problem and one that solving will both lead us closer to the experience of a metaverse and also to experiences that feel more connected and meaningful.

Spoilers? But also it’s from Yesterday’s Wordle.

The Rise of the Daily

No, I’m not talking about the podcast.

The part of the metaverse that I object to, that I find disappointing more than dystopic is the concept that the best we can do are shallow, visual representations of the real world. Equating physical presence with a visual copy of the physical world is such a letdown. This isn’t to say that there shouldn’t be visual components to these experiences, but there are so many more interesting ways to make a digital world feel permanent.

Ok so sure the metaverse doesn’t have to be photorealistic, but Wordle is still this single-player game. The best we can do is play alone and compare scores. I would like to introduce to the concept of the daily run. The daily run definitely predates roguelikes (crosswords have existed longer than the internet) but the idea of a programmatically generated game creating a single “run” that you compete on is something roguelike games like Spelunky popularized. It’s a concept discussed fairly extensively on The Eggplant Show (a weirdly named but genuinely great game design podcast). A roguelike is an algorithmically generated game that you can compete on over and over, either for high scores or for discovery. But the challenge with roguelikes is that you are always playing a “different” game than everyone else. The same meta-rules are the same, but the actual experience can vary wildly. What the daily does is create a single shared seed that will live for 24 hours that people can play to compete and compare themselves against each other.

The reason that these games constitute more of a shared reality is that unlike something like a book (like say Lord of the Rings), you’re not spawning your own ideas in your head. You’re all reacting to the same shared ruleset. That shared ruleset is important because we have to talk about what actions we took to overcome that ruleset, not just what we thought about a particular representation. The differentiating factor is the share objects, verbs, and experiences that guide us.

A daily is kind of an “asynchronous metaverse” rather than competing directly against other people, you’re experiencing the same functional world and so you can compare notes and learn from one another. The exact type of thing that a shared reality might aim to accomplish. This is taken to the extreme in a game like Phantom Abyss where you get to learn from the ghosts of people who came before but are competing against the future of the people who will come after. Phantom Abyss is similarly cool because it has an interesting take on that concept of presence.

Stepping into this daily concept is what makes Wordle’s sharing feature is so clever. At the end of every game, we create this small piece of presence. This nod towards the existence of a shared reality that we have all encountered and dealt with. It’s a tangible feeling of output that is “non-fungible” as it relates to who we’re are and what we’ve done. The squares tie in our heads to at least the concept of the board, the place where we play Wordle.

My family is full of people who love word games. Boggle was close to our most played game as a family, my dad still does NYT Crosswords daily and before we learned about Wordle we’d have regular conversations about another daily spelling game, Spelling Bee. But without a share feature, it was pretty hard to talk about the game at all. Having those physical representations helps create connections where abstractions create a barrier that is hard to overcome.

The small blocks seem so innocuous, but in a lot of ways, they’re miles ahead of what other games are doing to create a shared narrative and a sense of collective experience.

A Quick Aside About the Design

So I know this is ostensibly about the social impact of Wordle but I want to quickly geek out about the design. Feel free to skip if it’s not interesting to you.

Derek Thompson’s Hit Makers talks about the human relationship to new technology. He calls it MAYA (Most Advanced Yet Acceptable). A MAYA technology is advanced enough to be novel and exciting, but not so advanced we don’t understand how it can fit in our lives. I’d like to propose a corollary for games Most Abstract Yet Attributable (yah it’s a mouthful but there aren’t many A words that are a simile of concrete). It’s the idea that games that are abstract enough to give us a lot to play around with, but not so abstract or dense that they’re hard to understand or complete.

Wordle makes a number of smart choices that shrink the scope of the game to the point that it’s challenging but can still be understood intuitively. Firstly, the game just asks that you know a five-letter English word. It can be (almost) any valid word. From a UX/marketing perspective that’s such an easy get. There are reasons why that might be challenging for a variety of people, but in terms of expanding the scope of the audience that can start your game, it’s hard to get much better than that. Next, the game gives you all this information about the letters: green if it’s the right letter in the right spot, yellow if it’s the right letter wrong spot, and grey if it’s the entirely wrong letter. This information lets your brain start thinking about all of the different shapes of syllables and words that you know. Each clue unlocks some part of your relationship to the math/experience of the English language without explicitly asking you to think about the relationship between the syllables in the English language. And finally, the number of letters you can guess is a really tight 30 squares. But 30 squares also means that in your first 5 guesses you can guess almost every letter in the alphabet should you so choose. Double letters throw a kink in this plan, but even assuming you got 25 grey spots, your chances of abstract failure are pretty low. This means that if you don’t get the word you feel like you were the reason, not the game being overly abstract or hard to parse.

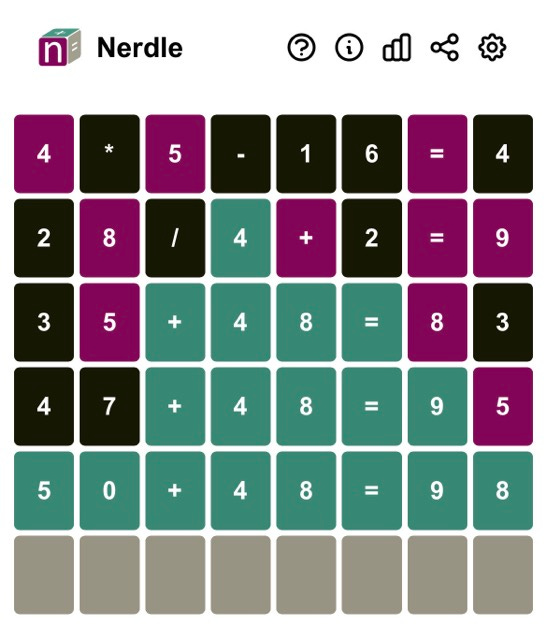

If you look at some of the other wordle-like games that have popped up like Globle or Nerdle. In either case, you’re expected to come with a lot of knowledge you might not have, or do a lot of thinking and processing to get to the point where you can even start, much less solve the problem.

I don’t think it’s a mistake that word games keep hitting it big. Words are in fact one of our most pervasive shared realities and one of the systems that we are most likely to feel comfortable playing with. But as The Why Axis notes, there’s actually a lot of designer choice under the hood to make Wordle feel great.

And unsurprisingly there’s a lot of great math underneath the hood here too:

But Isn’t This Just a Huge Fad?

If you’ve gotten this far, maybe you’ve bought into one or even both of my arguments. Wordle produces these cute artifacts of presence and even though they’re separate experiences and similar logic creates a sort of shared reality. But then you say, why isn’t Wordle similar to something like Pokemon? It’s a huge fad, but no one would accuse it of being a metaverse.

To that I would like to say, I think Wordle represents a fundamental shift in how we think about ourselves as digital citizens and I really hope more game designers will pay attention to that.

For a fun experiment try to imagine two monks in the 14th century playing a physical wordle-like-game. One knows the answer and shades in answers to give clues to the other who’s writing the word on the parchment. It's technically the same game, but it's definitely not the same game. Wordle’s share mechanic can feel like it crept out of the early web. It’s free and open (it’s not even a “true” app!) and the share links are these cute little squares not redirecting you to some walled garden where you can put in your credit card to try out the latest game.

But like Pokemon represented something of a shift in the relationship between traditional media (like movies and books) towards games, Wordle represents something of a shift in how much we see, share, and ask from our digital spaces. Wordle caught on in part because of the ubiquity of multimedia texting with Twitter, Whatsapp, iMessage, and the like. It exists in a world where we want to show the results of the things we do and in a world where we’re trying to reclaim some of that closeness and reconnection to the people around us. And it even might save some people from Qanon?

It may seem incongruous that such a simple and wholesome game could have such a dramatic impact on a QAnon follower, but the structure of QAnon–where followers feel part of a community and share their “research” with each other–means the two share a lot in common.

“Wordle appears to have done a very similar thing [to QAnon],” Joe Ondrak, head of investigations for Logically, an organization that combats online misinformation, told VICE News in a message. “A community has assembled, sharing an interest and understanding, who are meeting to discuss strategies and ways of understanding it further.”

Leaving You With Something

My goal here wasn’t to convince you that NFTs are good or bad or to create some sort of pie in the sky think-piece about how games will save us (there’s like a 50/50 shot a stumbled my way into a bad version of that though, sorry). Rather it was to show how there are some genuinely exciting components of metaverses that could create a cooler, weirder, and more connected to who we are and the people we want to be with. I’m hopeful that Wordle will inspire more game designers to find ways for us to share our histories with the games we play.

The trick, I think, is to focus less on the ownership and absolute permanence, and focus more on small artifacts that connect the experiences we’ve had in the past to who we are right now. Those wind chimes are fungible. At some point (maybe the heat death of the universe, who knows!) they won’t reside at my childhood home or they won’t be metal and wood. The point isn’t that it lasts forever, it’s that it lasts long enough to be meaningful to me.

The optimism of Wordle's accidental metaverse is that it's small enough for us to wrap our heads around. Maybe it can show a generation of designers how different shared experiences can be created beyond simple facsimiles of the world we already have. And maybe it can help us think about how we can live in and around each other's metaverses more effectively.