What is selling out, anyway?

The expectations we set for being a "true indie" are too large

As a continuation to a previous article about how I find games to play, I want to talk about the promise and peril of being a public creative.

What Happened?

In the last couple of months a couple of things happened within the board gaming space that generated an amount of commentary and cynicism.

Shut Up & Sit Down (SUSD) announced a publisher partnership with Play to Z, to select and promote designs. While they’ve done collaborations with publishers (CMYK) in the past, this represents a significant expansion in that type of relationship that is fairly different and new for them.

Stonemaier Games announced the board game Finspan. The third in a now trilogy of “span” games that started with Wingspan, and also includes Wyrmspan.

I’ve written about Wingspan before, and it’s a great game with a ton of crossover appeal. You’re basically collecting a variety of different types of birds and scoring points based on their relationships to each other. Finspan seems like an expansion of that mechanic in the aquatic space.

The Outcomes

My cursory understanding is that Finspan has created quite an uproar on Board Game Geek for some and excitement for others. And the Shut Up and Sit Down announcement has created more murmurings of discontent and concern but no outcries or accusations. The SUSD team wrote an incredibly thoughtful response that I highly recommend reading.

My Reaction

This caught me off guard to be honest. I would’ve expected much more consternation about a potentially tricky publisher relationship and much less about what feels like a fairly natural progression for a series to go in.

What makes both cases similarly, however, is the concept of independence and fan expectations. Specifically, it’s not just about the relative independence of a given creative personality, it’s about how they act in the world, and what sorts of business decisions they choose to make (or not make). And specifically, the idea of selling out isn’t just about exchanging their personal brand for a large sum of money, but about taking advantage of business opportunities or behaving in a way that a larger corporation might.

In no case am I trying to sanction the flame or hate that has come in either team’s direction.

I don’t think these relationships are unique to gaming either, I think similar conversations around being consumers of music or film are also going on. For a lot of people who are hobbyists, enjoying art isn’t just about being interested in novelty, there’s also a tinge of defensiveness to it now, as retreads become ever more common. In an era where companies like Microsoft buy Blizzard mostly for Candy Crush, or Magic: The Gathering creates a multi-year relationship with Marvel, picking and choosing the people we want to follow can feel like a decision to rebel against those impulses towards sameness and brand integration, which become proxies for greed.

And the nature of following someone on the internet has gotten so strange (so much ink has already been spilled about the nature of parasocial relationships I’m not going to dig too far into this) that picking someone to follow can feel not just like an admission of interest but a personal relationship you’re committing to. So we end up responding to people breaking those “commitments” with a sense of betrayal because of perceived closeness.

But, it also places unreasonable burdens on creatives to act ethically, pursue fulfilling work, be personalities on the internet, and also uphold values that we have placed on them. This isn’t to say we shouldn’t have accountability, just that, the accountability should be about the actual outcomes we care about and not about the signals they might represent. Which, admittedly, can be tough given the amount of information flying around. But, I think we owe to the people trying to do good work to at least put that much effort in.

The Reviewer/Reviewee Barrier

Let’s start with SUSD. Tabletop gaming has a fairly large problem with the pay to play space. Pay to Play, in the case, means that many content creators won’t leave a review for your kickstarter or your game unless you directly pay them, with upfront costs and fees. And the reviews themselves are all… pretty dry, quite frankly. Often on gaming Kickstarters you’ll see reams of positive reviews that seem quite similar to the back of a book jacket: kind platitudes that don’t tell you much of anything about the game. There are also the “con hauls”. These are posts to instagram and social media where content creators will highlight all the games they “picked up” at a convention, while conveniently not mentioning the fact that none of those games were actually paid for.

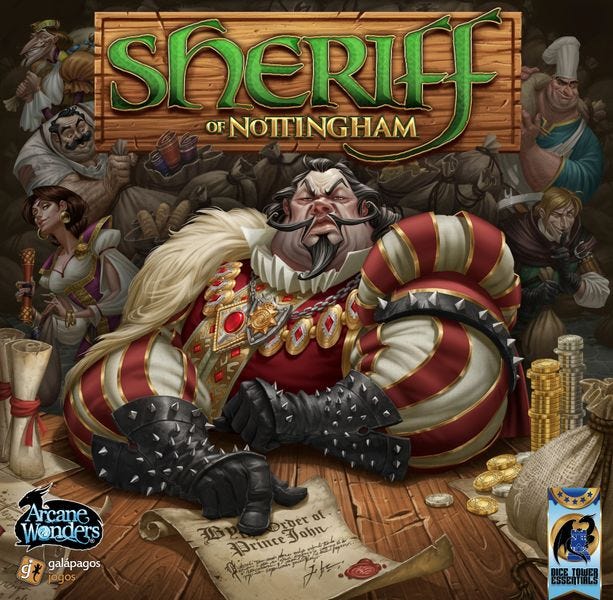

But this also isn’t the first time a beloved reviewer has entered into a similar arrangement with a board game publisher. The Dice Tower (probably the most recognized name in board game reviews) has a relationship with Arcane Wonders where Tom Vasel will pitch them games he thinks are worth highlighting or bringing back, and Arcane Wonders will consider getting them published.

My initial emotional reaction to the SUSD announcement was a mix of excitement and disappointment. On the one hand I have a lot of trust in their ability to recommend great games, and I think the games they’ve announced seem really neat. On the other, it means fewer insightful and funny reviews (probably? maybe?) and a further complicating of their standing and relationship to the games. On the other hand, as their post so eloquently explains, I can absolutely empathize with the desire to move further upstream to make a positive (and potentially larger) impact on the board gaming hobby.

To directly address some of the cynicism I’ve seen - this isn’t just us whacking our logo on some boxes. We are picking the games, using our influence to bring back designs that otherwise might not see the light of day, AND using our clout to ensure that long-awaited reworkings don’t end up being expensive “deluxe” boxes full of plastic bloat.

A lot of the questioning of SUSD comes down to this idea that there should be a barrier between publishers and reviewers, so reviewers can give an honest assessment of the games without untoward influence. This is one area where I think the differences between board games and other forms of media really does stand out. For games, unless you’re part of a gigantic outfit like Polygon or Kotaku, you’re not going to be giving a comprehensive review. You’re not even going to be giving a review of what people might consider the most popular games of the year. So the element of bias is already coming in when it just comes to which games are getting shown in the first place.

The barrier made sense in a world where there were explicit delineations between the sources of news and commentary and the sources of art. Like if Roger Ebert had a financial relationship with Universal Pictures, I think that would’ve been a real problem. But, Universal Pictures can already just host its own YouTube channel now (probably already pays influencers for positive reviews), and the entire relationship between reviewers and publishers has already been completely inverted, anyway. In that world, what’s the benefit of holding reviewers to a standard that would appear to benefit the more unscrupulous publishers, anyway?

It feels possible to separate out pay for play (bad) and entanglements (complicated) without throwing out the work of people who by all measurements appear to be genuinely committed to making the hobby better.

How Many Sequels Is Too Many?

The other element that connects SUSD and Finspan is that Stonemaier games is a fairly popular YouTube channel for game design insights.

Finspan has garnered at least some amount of vitriol for being a “sellout” or “cashing in” on the brand because it’s taking advantage of the familiarity of the game to sell more boxes to people.

Speaking as someone who wasn’t particularly in love with Wingspan, I find this line of thinking quite baffling. Finspan appears to be a genuine evolution of the series that’s made with care and attention. Notably, the mechanic of adding more fish further down in the ocean seems like a really smart recontextualization of the ideas of both Wingspan and Wyrmspan within the theme it’s trying to execute!

But I think that sort of parasocial relationship is where some of this vitriol comes from. Stonemaier isn’t “just another game company”, Jamie is a trusted face for design insight. So the critical eye becomes harsher. Like, yes I’m sure there’s a financial incentive here to release a game that’s already got a lot of brand awareness around it, and has an opportunity to break out and reliably sell. But Stonemaier is still producing games like Apiary (a game about space bees!) it’s not like they’re retreating only into safe content.

This is one of those areas where “playing the game” feels especially challenging for creatives. You want to both cultivate a following so that you can pursue interesting ideas with the support of a customer base, but then you can get trapped within the emotional expectations of that customer base, if you let it.

The Cynicism Runs too Deep

Ultimately, I just think the expectations for smaller content creators is just way too high. We expect them to not just survive but also be paragons of the highest values that we expect. And when larger companies do cynical things, we role our eyes and support them anyway because of course why not. This seems thoroughly backwards.

Commercial, But Not Too Commercial

The people who seem to be the most successful produce games that are an interesting mixture of broad appeal with interesting artistic perspective are quite nimble at balancing commercial and business concerns while having a clear artistic vision. This is not to say that everyone should act this way. I don’t think it’s excellent if everyone’s trying to build a following, game the algorithm, and produce optimized content. But, I also think we should give some grace to the folks who try, while still broadly fitting within the values of creativity and artistic honesty that we admire so much.

The Games

To that end, the games I want to highlight games that are created or published as a result of these sorts of reviewer-publisher overlap.

Sheriff of Nottingham

Sheriff of Nottingham was one of the first games announced in the Arcane Wonders Partnership with The Dice Tower. The basics of the game play a lot like BS, but instead of trying to play cards on a pile, you’re trying to “smuggle goods” or trick the sheriff. The little baggies that you put the goods in each round help set the scene. Highly recommend this game!

Thronefall

Thronefall is the work of Grizzly Games and one of the devs, Jonas Tyroller, put together a playlist documenting their development of the game. He talks a lot about making good games as an indie dev and “following feedback”. I think his work is quite insightful, and also he seems quite adept at using his following to create a positive reinforcement cycle to promote the games (which are excellent). Thronefall is a sort of tower defense style game mixed with MOBA/RTS elements, where you have a king character that you can use to marshal troops and direct resources.

Tactical Breach Wizards

Tactical Breach Wizards was one of my favorite games of last year. You can read about it more below.

Tom Francis was a games journalist before becoming a fulltime game designer and ripping off a string of just absurdly good games (Gunpoint, Heat Signature). He also continues to post game design thoughts on his Youtube channel, which I highly recommen as well.