Paper Computers

The joys of digital gaming can be captured in a permanent format

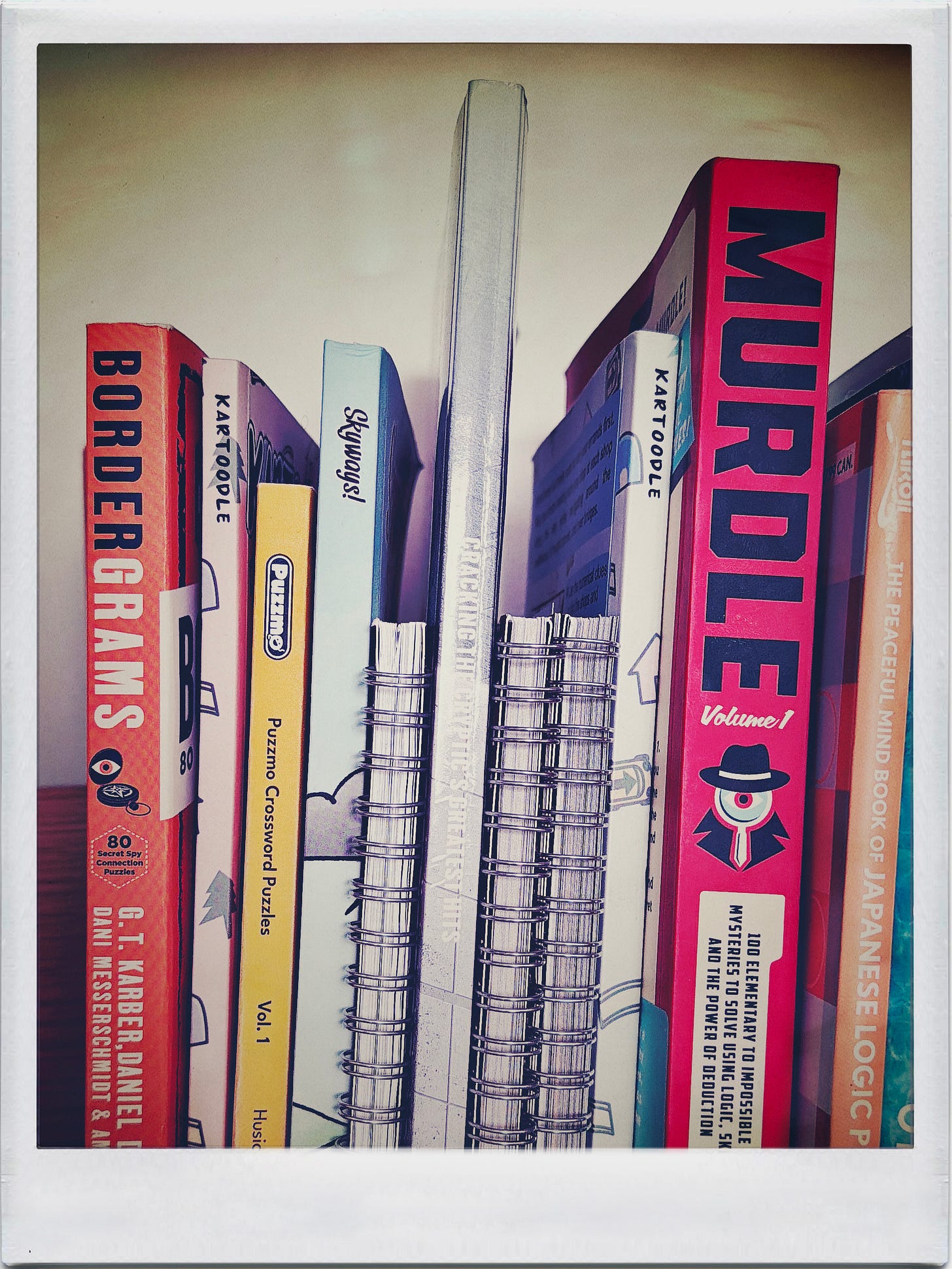

10 puzzle books sit on my living room bookshelf. Some are index card sized and spiral bound, others are tall, most are thin, like a novella. A casual observer probably wouldn’t know they were puzzle books.

I never imagined I would ever be the owner of that many puzzle books.

As a kid I thought puzzle books were silly and unserious. The primary puzzle book I saw every where crossword puzzles. These seemed designed to pass time on an airplane by mashing words together not thoughtfully crafted experiences. And the math games, they seemed like fun artwork aimed at the concept that you could teach your child math just by buying them these books. They were beautifully illustrated, but the design pieces were less designed so much as mathematics problems wrapped up in art.

Nevertheless I now own multiple of these things. In part because I have a deep and abiding love of paper and pencil. The through line on my love of puzzles, of tabletop games, and probably even baseball is this idea that thought made manifest on paper is magical.

In an abstract sense it might seem strange that paper puzzles are still not only being produced, but being produced by video game designers, but I think these things are quite linked! At some point the theoretical boundaries between where the rules happen to run. And exploring running rules on the human brain is a different way to think about problems to solve. And, though on a smaller scale, puzzle books have gone through a similar explosion of indie development that tabletop and digital games have.

My naive perspective is that these things are quite linked. Access to cheap publishing tools and on-demand printing spurred on by advancements in computer technology make doing interesting things with paper much more within reach. And the advancements in User Experience can be applied (in more limited ways) to paper products in addition to digital ones.

For the games I own, three are the spiral bound games from Blaz Gracar. Three more are from Adam Bontrager (Two Kartoodles and a Skyways). There’s a Murdle and a Bordergrams (kind of pen and paper Connections by the publisher of Murdle). There’s the Puzzmo puzzle book by Puzzmo. There’s the first Cracking the Cryptic book and the Nikoli puzzle book which is full of all of these strange and wonderful Japanese style puzzles.

Digital Feel

When I play these puzzles I can feel the action and reaction play out in my head. It’s anticipatory play, but what’s on the paper leaves enough connective tissue for it to feel alive and real.

There’s an experience and a progression and an opinion attached to them. They feel like they’re supposed to be fun. Fun is an elusive thing to try to describe but even at a young age I felt very confident that simply declaring something as “fun” wasn’t enough to make it so.

It’s that digital “feel” that attracted me to these games. These were all games that either figuratively or literally feel like they could be easily implemented on computers.

It’s easy to describe how computers shape a game. You can make infinite marks on a computer without ever damaging the paper underneath it, and the computer can tell you whether you’re right or wrong close to immediately. How is it possible that games like these can do similar things?

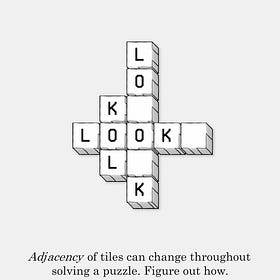

Size seems to play a huge role. For example the Puzzmo Crosswords are all “Midi” sized. Large enough to be bigger than the 4x4 grid but small enough that each individual solve takes you a meaningful percentage closer to the end. Blaz’s LOK, which LOK Digital I reviewed, also seems to similarly shape the puzzles in a small enough size that any given potential solution is both able to be captured in memory, as it were, and also meaningfully takes you towards the solution once you put pen to paper.

Great Mobile Games are Like Digital Haiku

The hardest thing about mobile gaming, I think, is twofold.

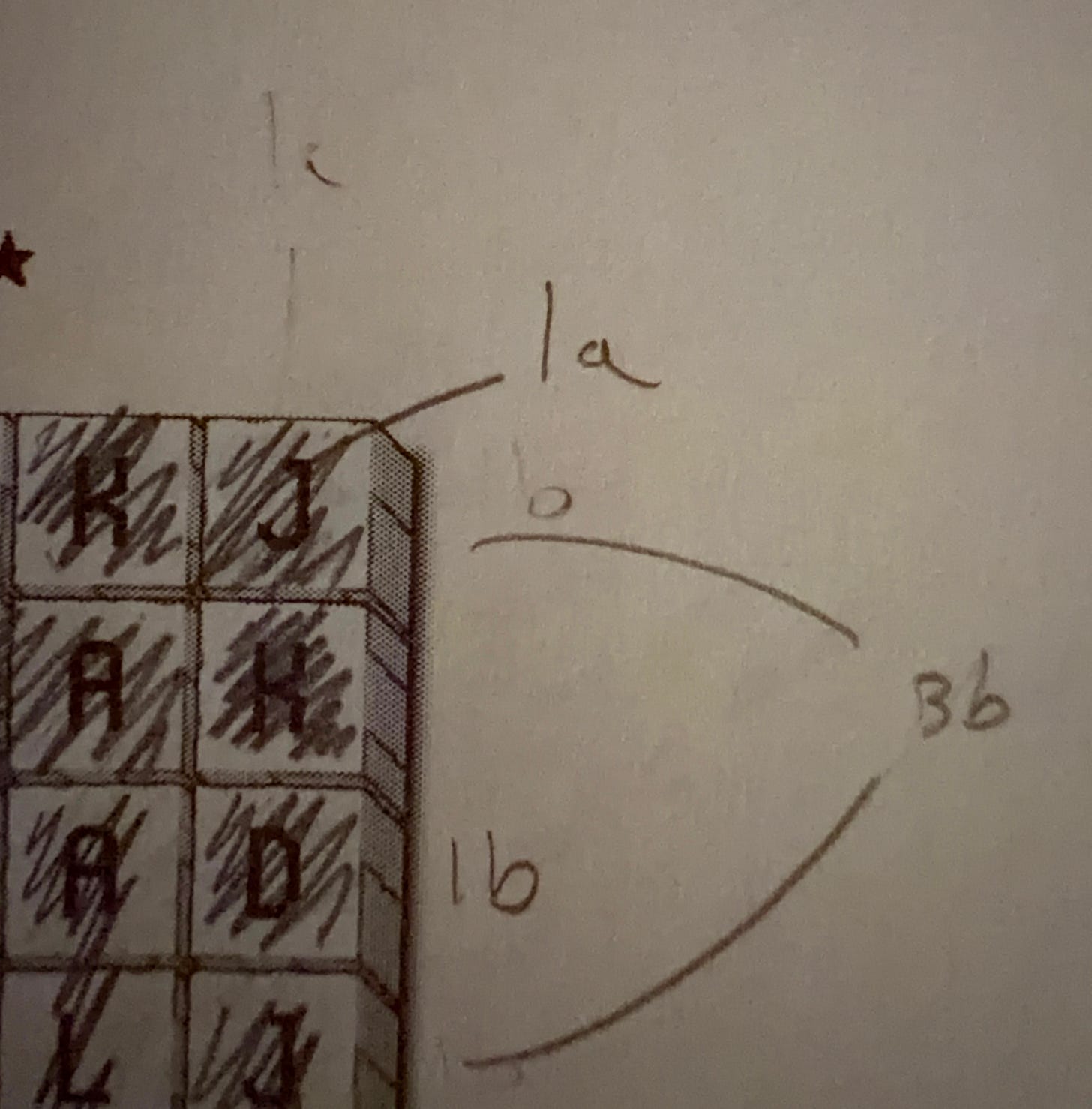

Many of these games also play with themes of teaching and rules interpretations. LOK and ABDec especially don’t layout the rules for you at all. You have to explore and understand them. As Dan Thurot, on a recent podcast, mentioned that Amabel Holland mentioned, part of the exploration of the rules in the paper game is the possibility that you can be wrong. And in fact I’ve had this exact experience. Being wrong about a rule and later going back to learn why I was wrong. There’s a page in LOK that describes “invalid” puzzles and asks you to explore why they’re wrong. This type of thing is nonsensical in a video game.

Each of these things makes me feel like I’m “in communication” with the game while I play, even though there’s no computer to send information back at me. I’m holding the rules in my head and exploring them simultaneously, in a small enough format that allows for fun interplay and exploration. It’s a UX hack that shrinks the puzzle down to a size where any potential input can be easily thought through and feedback can be given. It’s brilliant and clever.

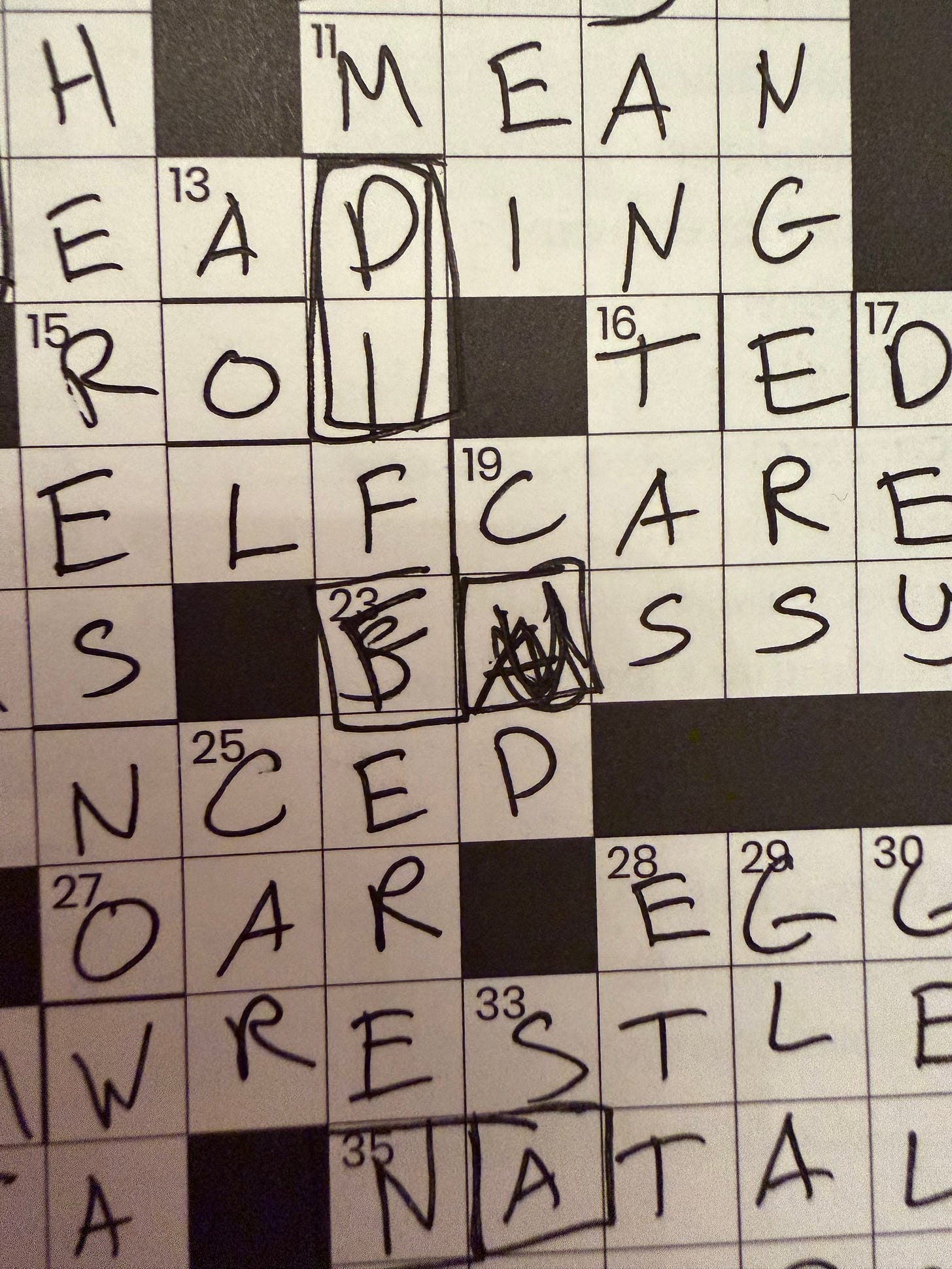

Making a Mark

Ultimately, I think the charm of puzzle books is their permanence. You have a record (in some way) of every right and wrong move. And that ties you to it in a unique way that computer puzzles cannot compete with. When I finish a puzzle on Puzzmo.com the game looks like the way that any number of people have seen (setting aside the less pure puzzle for just a second), but when I finish a puzzle book, the folds, the bends, the way that the book bows open at the page I had open the longest because I was struggling with. Those are all unique to me and it create a memory that lasts a lifetime.

Are there any of these games that your dad could figure out?